FILM

FILM In Which All Of The Men Were Such Interesting Animals

Tuesday, September 5, 2017 at 9:36AM

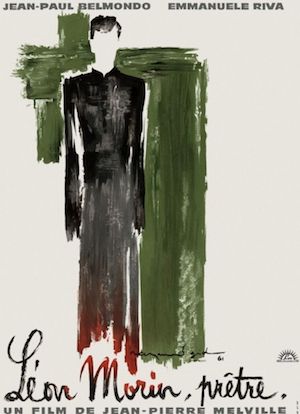

Tuesday, September 5, 2017 at 9:36AM This is the fourth in our ongoing series returning to the films of the French director Jean-Pierre Melville.

Meander

by ETHAN PETERSON

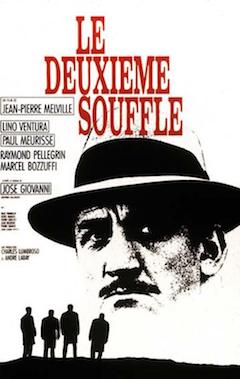

Most of Jean-Pierre Melville's films are tight, austere masterpieces. Le Deuxième Souffle consists of a movement in an opposite direction. "A dishonest, aimless meander," wrote Jean Narboni, a noted Godard admirer, of Melville's 1966 effort. At 140 minutes, it is Melville's longest film; but Army of Shadows which approaches it in in length, contains the added intrigue of being a sorrowful, moving, colorful historical film about Melville's time in the French resistance. Le Deuxième Souffle has none of those advantages. It is a simply the most hard-boiled crime film ever made.

Most of Jean-Pierre Melville's films are tight, austere masterpieces. Le Deuxième Souffle consists of a movement in an opposite direction. "A dishonest, aimless meander," wrote Jean Narboni, a noted Godard admirer, of Melville's 1966 effort. At 140 minutes, it is Melville's longest film; but Army of Shadows which approaches it in in length, contains the added intrigue of being a sorrowful, moving, colorful historical film about Melville's time in the French resistance. Le Deuxième Souffle has none of those advantages. It is a simply the most hard-boiled crime film ever made.

There is a lame cliche that a filmmaker is trying to make the same film again and again, getting closer every time. For Melville, that film was John Huston's crime drama The Asphalt Jungle. With Le Deuxième Souffle, Melville not only approached the raw mood and heist plot of his favorite film, he exceeded it considerably when it came to technical craft, depth of character, and outright excitement. While a few critics seemed to shrug off Le Deuxième Souffle, most were gracious enough to recognize there had never been anything quite like it before.

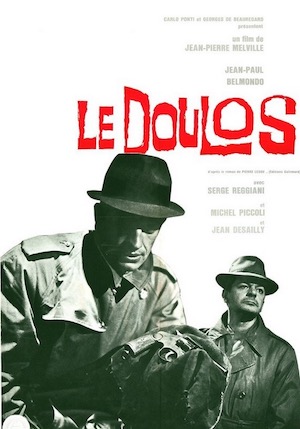

Melville first tried to put Le Deuxième Souffle together with a completely different cast, ending up in litigation with his producers. When he tried it again in 1965, Lino Ventura was now playing the lead role instead of the considerably less mercurial Serge Reggiani. Both men were very accomplished, understated actors, but Ventura was not only the more physical performer, he was ideal for the role of Gu Minda, a career thief who emerges from prison for one last gasp of freedom.

Ventura and Melville, both headstrong individuals, eventually had a falling out on the set of Army of Shadows. Too bad — the Italian actor and the Jewish director were in many ways an ideal pairing. Ventura needed overwhelming instruction lest he become a hammy parody of a swarthy Mediterranean, and Melville was nothing if not hands-on. At times he would force actors to watch take after take of their scenes, until he totally dissociated them from their abilities. It was at that point when he began to build them back up in the way he preferred.

Gu Minda is a doomed character who escapes from prison in the near silent scene that opens Le Deuxieme Souffle. He has one person in Paris who he can turn to — it is never precisely clear whether this is his girlfriend or his sister, but her name is Manouche (Christine Fabréga).

Manouche is one of Melville's very best characters, and in her scenes alone, we get a glimpse of another peripheral story, deeper than a killer's could ever be. At times the pair seems close enough to be an incestuous pair of siblings. In other moments, like a candlelight dinner they share in the attic where Gu hides out after his escape, it seems clear neither expects much from the romantic relationship other than kindness. This afterbirth of an arrangement only lends more feeling to the idea everything in Le Deuxième Souffle, including Paris, was dying of something.

Positioned around this relationship is a stellar cast of criminals and cops. Their closeness and interchangeability makes it so that when Gu is finally tricked into incriminating himself, we can barely blame him for being deceived. The rest of the diverse cast (in ethnicity as well as style) is highlighted by Michel Constantin, a Russian-French actor who portrays Manouche's bodyguard and Gu's friend. If it were not for the completely reasonable behavior of all the people in this milieu, you would be forgiven for thinking Le Deuxième Souffle consisted of a raw, elemental style over substance.

Melville's feel for the fashion of crime turns Le Deuxième Souffle into his most pleasing visual feast. Even in black and white, the speed with which violence regularly occurs inside small rooms and hallways, out of doors and on the road, is visually stunning and sometimes outright alarming. Watching The Asphalt Jungle in close concert with Le Deuxième Souffle, I was stunned by how much more of Paris there is in the latter than San Francisco of the former. It is like one movie shows us a snow globe and the other a life-size diorama.

The film's climactic platinum heist is all the more highly anticipated because Melville forces us to wait for so long. Although Le Deuxième Souffle does drag at times, the director always snaps his audience back into the mise en scène with a bang. Gu's specialty is his use of guns, and the one-time professional wrestler looked athletic enough to fistfight even at forty-six years of age.

Still, Gu recognizes that he is an old man with only so much left to give. "When you are young, you think that men are interesting animals," Melville told Rui Nogueira in his marvelous collection of interviews with the director, Melville on Melville.

I have no illusion anymore. What is friendship? It is telephoning a friend at night to say, 'Be a pal, get your gun and come over quickly' - and hearing the reply, 'OK, be right there.' Who does that? For whom? Until he is thirty-three, a man is convinced he'll always be twenty years old. Then one day he looks at himself in the mirror and sees that the years have gone by.

Ethan Peterson is the reviews editor of This Recording.